Charlie’s Sandwich Shoppe: An 87-Year Retrospective

Written by Irwin Levy, Friends of Titus Sparrow Park Board Member

A Story Too Big for One Blog Post

Attempting to write about Charlie’s Sandwich Shoppe would be a daunting task for a professional writer, much less yours truly, especially within the confines of an all too short blog post. The stories alone could, and have, filled a book. Charlie’s was iconic, larger than life, and far more than just a neighborhood business. Where to start?

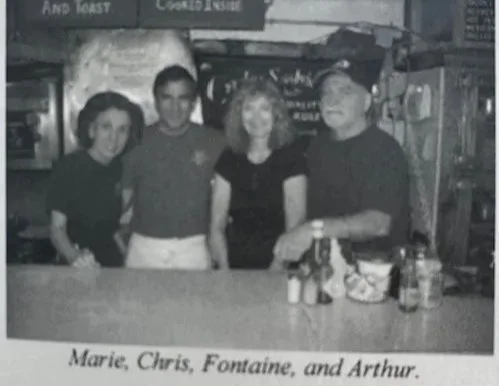

Thankfully, I had some help from Justin Manjourides, a South End resident and Associate Professor of Biostatistics at Northeastern University. He is also the grandson of Christi, son of Arthur, and nephew of Chris, Marie, and Fontaine. Those five names represent two generations and 87 years of Charlie’s, 69 of those years as its owners, from 1927 to 2014. Let’s call it the Manjourides era.

The Early Years

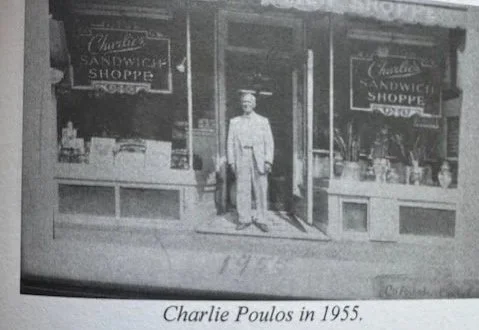

Charlie Poulos opened Charlie’s in 1927, and Christi Manjourides was his first employee. Charlie focused on the front of the house, while Christi was the chef and baker. Charlie’s was open 24/7, so each worked a 7 to 7 shift, Charlie during the day and Christi overnight.

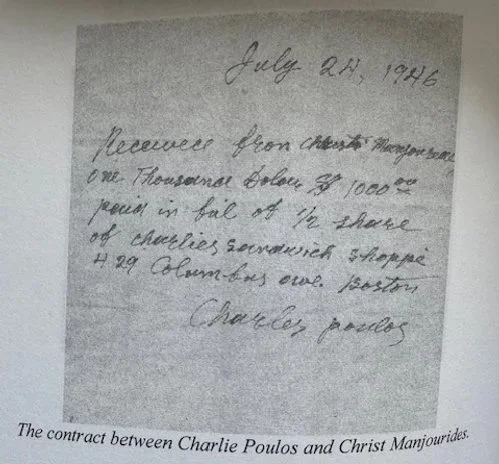

By 1946, Christi purchased the building and a half share of Charlie’s, the “contract” handwritten on a piece of paper that still hangs in the restaurant today. From the beginning, Charlie’s was open to everyone, at a time when that was far from the norm. The South End was the jazz capital of Boston, and African American musicians playing the clubs frequented Charlie’s as a welcoming space.

Boston’s Black musicians were part of the American Federation of Musicians Local 535, a segregated union that existed alongside the white union, Local 9. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first predominantly African American union, also played a vital role in this history, a prominence reflected today in a permanent exhibition at Back Bay Station. That both unions held their meetings above Charlie’s Sandwich Shoppe speaks volumes.

Life Inside Charlie’s

Justin shared his own memories of Charlie’s as a young teenager, bussing tables, washing dishes, and working the cash register after school and during summers. He was the proverbial fly on the wall, seeing and hearing everything. There was no such thing as too much family, at least not overtly. Arthur lived on the fourth floor above Charlie’s, and Uncle Chris on the third.

Justin watched his dad and uncle work together like a well oiled machine. Talking was not always required. They had a cadence and seemed to anticipate each other’s moves. There was, however, plenty of back and forth between staff and customers, especially the regulars. If someone let slip a worthwhile bit of neighborhood news or gossip, Arthur and Chris would grab onto it and not let it go, sharing it with everyone. That exchange became an essential piece of Charlie’s folklore.

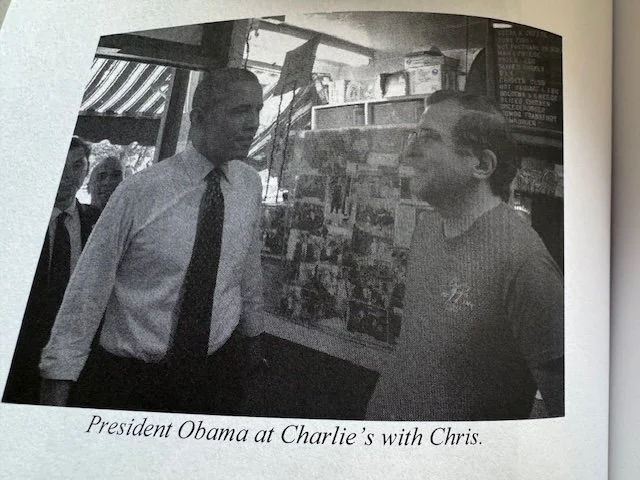

It is also worth noting that the tables, like the counter, were communal, a Charlie’s tradition that no longer exists. For 87 years, bankers sat next to felons who sat next to politicians who sat next to prostitutes who sat next to celebrities.

A Lasting Legacy

For me, that is the real legacy of Charlie’s during the Manjourides era. Charlie’s Sandwich Shoppe was a place that welcomed everyone equally, no questions asked, a brick and mortar metaphor for what the South End always was and what it continues to strive to be. That legacy reminds us why places like Charlie’s matter so deeply—and why we carry their stories forward with us.

Thank you for reading our neighborhood stories and helping us celebrate the people and places that have shaped the South End.